Mary Henderson tried to move the White House to be closer to her house. That’s worth repeating. Mary Henderson tried to move the White House to be closer to her house.

There are few people more influential to their neighborhood than Mary Henderson, elevating Columbia Heights from a largely rural exurb to a magnificent urban center, complete to resplendent embassies and her own personal castle.

Mary Henderson was born into wealth, the niece of Senator Samuel Foote of Connecticut and married into more wealth, becoming the wife of Senator John Henderson, famous for introducing the 13th Amendment, which banned slavery.

John Henderson made a fortune in the Missouri bond market, but it was Mary Henderson’s civic engagement and activism in the real estate market that made a lasting mark.

When the Hendersons moved to DC, they decided to build a brownstone castle on the crest of Meridian Hill in 1890. The Evening Star reports:

Mr. Henderson’s house is modeled on the style of a Normandy castle and is built of Connecticut brown stone. It has square towers and rounded recesses, balconies, porticos and archways of stone. Inside the hall is decorated in green and mastic color, in the Moorish fashion, and about the door casings, windows and ceilings are engraved mottoes from Mahomet’s [sic] Koran in the Arabic characters.

The Henderson Castle was built in the Romanesque style, with bold square towers and an arched entry way. The “castle” added much needed architectural diversity to a largely neoclassical city (let’s pretend the rampant Brutalism of the L’Enfant Plaza area doesn’t exist).

The castle-like appearance of the estat e coupled added to Mary Henderson’s modern day memory as a sort of american duchess in Northwest DC.

e coupled added to Mary Henderson’s modern day memory as a sort of american duchess in Northwest DC.

And Henderson’s land holdings were impressive, but what she wanted to do with those holdings were more impressive. She wanted her castle to be the centerpiece of burgeoning diplomatic enclave in Northwestern DC. She wished to remake 16th Street into perhaps the most impressive avenue in the Western Hemisphere:

“Something like the Champs Elysees, Sixteenth Street is central, straight, broad and long…. Its portal at the District line is the opening gateway for motor tourists to enter the Capital. On the way down its 7-mile length to the portals of the White House, each section of the thoroughfare will be a dream of beauty: long impressive vistas, beautiful villas, artistic homes — not only for American citizens but diplomats. Whatever there is of civic incongruities will be wiped out. It will be called Presidents Avenue .”

-Mary Foote Henderson, “Remarks About Management of Washington in General and Sixteenth Street in Particular.”

Henderson wanted to have busts of each President and Vice President to line the avenue leading down to the White House, reminiscent of the wax masks of ancestors that Romans hung in their atriums to remind them of accomplishments and failures of the past. She actually managed to convince Congress to change the name of 16th Street to Presidents Ave, but the name proved unpopular and congress changed it back the next year. No funds were ever appropriated for the busts.

In 1911, when Congress was debating where the Lincoln Memorial should be, Henderson offered Meridian Hill. She argued for a Memorial Arch, adding that 16th Street “may sooner or later be on the line of roadway which will connect the White House with the Gettysburg Park”.

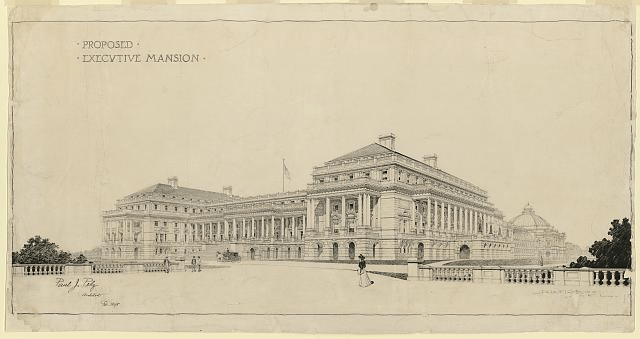

Even more audacious was her plan to move the White House to 16th Street. She believed the White House to be a modest structure, not befitting of the office it holds. In a way, she may be right. Compared to other, less powerful nations, the United States has a very modest dwelling for the head of state, but that of course is part of the American political tradition.

Somewhat reversing course from Washington and Adams, Thomas Jefferson purposefully shunned much of the pomp and circumstance of European monarchies. He dressed more informally and even went so far as to walk to formal appointments with diplomats instead of taking a stage coach.

Mary Henderson would not have let this dressed-down, faux-everyman Jefferson in the front door.

“The White House is not a small dwelling. It’s too big to be a symbol of a modest central government,” Mary Henderson might say. “So if we are going to go big, let’s go REAL big.”

The new edifice would have bridged 16th Street. The traffic would pass through a triumphant arch (or bottleneck). Over the arch would be a great colonnade, a 500-foot loggia connecting the State Mansion (it isn’t too clear just who would love there) and the President’s Mansion. All in all it would include about 40 percent of the floor space of the 1900 Capitol.

–Washington Post, 1979

The potential rise in property prices along the 16th street corridor, much of which was owned by Henderson, may have had something to do with Henderson’s plan to put the White House right next door. Maybe not. Maybe it was just an excess of patriotism and love of architectural beauty that drove her advocacy. Probably not, but anything is possible.

Henderson shouldn’t just be remembered for ambitious but failed proposals. Her legacy is much greater than that. She gave land for the creation of a library on 16th Street, and she was successful in remaking 16th street into a diplomatic enclave. She commissioned the famous gilded age architect George Totten Jr. to build beautiful Beaux Arts embassies; some of which line Meridian Hill Park. See below for a slideshow of Totten built mansions taken by the author.

Mary Henderson shaped Merdian Hill park into the beautiful classically inspired shape it enjoys today. Originally, the McMillan Plan called for a large open park to straddle both sides of 16th street. Rather than a large but empty park, Henderson lobbied for a smaller but well designed park.

Although the McMillan Plan was articulated in 1901, it took until 1910 for Congress to establish Meridian Hill Park. The park was designed by George Burnap and later implemented by Horace Peaslee.

The park can be divided into two sections, upper and lower. The upper section is a flat green mall, and the lower section is a cascading fountain encapsulated by two winding staircases, leading to a reflecting pool. This style is typical of Italian Renaissance gardens, which sought to carve structure into the curves and twists of nature. It is a rare example of an heavily ordered park in the US, whose parks typically offer a slice of wilderness in the heart of a city.

Mary Henderson did not enjoy a happy ending. Her only son, John Jr. had trouble conceiving a child, so Mary Henderson promised him a large sum of money if he and his wife could produce an heir.

The couple did the only logical thing–fake a pregnancy, complete with elaborate padding and doctor visits. And as would only be possible in the 1920s, the fake pregnancy was a success (they secretly adopted a girl).

Only years later did Mary Henderson learn about the ruse, but she eventually reconciled with her “Granddaughter”, Beatrice.

This would not last.

When Henderson sought to donate one of her grander properties to be the residence of the Vice President (the offer was declined), Beatrice sued her, telling the courts that Mary Henderson was clearly insane and unable to decide what happens to her estate.

The courts decided that Mary was indeed sane, and Mary in turn decided that her granddaughter would not be getting anything and completely cut her out of the will.

Henderson died in 1931 without any heirs, her son dying in 1923 and his wife in 1907.

As a result, Boundary Castle was tied up in courts, leading to its prolonged state of disrepair and eventual demolition in 1949.

She could not move the White House next door. She couldn’t make 16th Street the avenue of presidents. She couldn’t get the Lincoln memorial on Merdian Hill.

But she did create an enclave of embassies in a previously barren neighborhood. She did shape DC natives’ favorite park. She did a lot land for a public library in Mount Pleasant. She did make a difference.

Her batting average lobbying in Congress was low, but when she hit, it was a home run. The Commission of Fine Arts memorialized her tenacious spirit perfectly:

Persistently she labored during four decades, persuading and convincing Senators and Representatives; single-handed and alone she appeared before committees of Congress to urge approval for the work of development. She won.